Early life

Artemisia Lomi Gentileschi was born in Rome on 8 July 1593, although her birth certificate from the Archivio di Stato indicated she was born in 1590. She was the eldest child of Prudenzia di Ottaviano Montoni and the Tuscan painter Orazio Gentileschi. Orazio Gentileschi was a painter from Pisa. After his arrival in Rome his painting reached its expressive peak, taking inspiration from the innovations of Caravaggio, from which he derived the habit of painting real models, without idealizing or sweetening them and, indeed, transfiguring them into a powerful and realistic drama. Baptized two days after her birth in the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina, little Artemisia became an orphan of her mother in 1605. It was probably at this time that she approached painting: Artemisia was introduced to painting in her father's workshop, showing much more enthusiasm and talent than her brothers, who worked alongside her. She learned drawing, how to mix colour, and how to paint. "By 1612, when she was not yet nineteen years old, her father could boast of her exemplary talents, claiming that in the profession of painting, which she had practised for three years, she had no peer." During that period her father's style took inspiration from Caravaggio, so her style was also strongly influenced by him. Artemisia's approach to subject matter was different from that of her father, however. Her paintings are highly naturalistic; Orazio's are idealized. At the same time, Artemisia had to overcome the "traditional attitude and psychological submission to this brainwashing and jealousy of her obvious talent". By doing so, she gained great respect and recognition for her work. Her earliest surviving work, by seventeen-year-old Artemisia, is the Susanna and the Elders (1610, Schönborn collection in Pommersfelden). The painting depicts the Biblical story of Susanna. The painting shows how Artemisia assimilated the realism of and effects used by Caravaggio without being indifferent to the classicism of Annibale Carracci and the Bolognese School of Baroque style.

Rape by Agostino Tassi

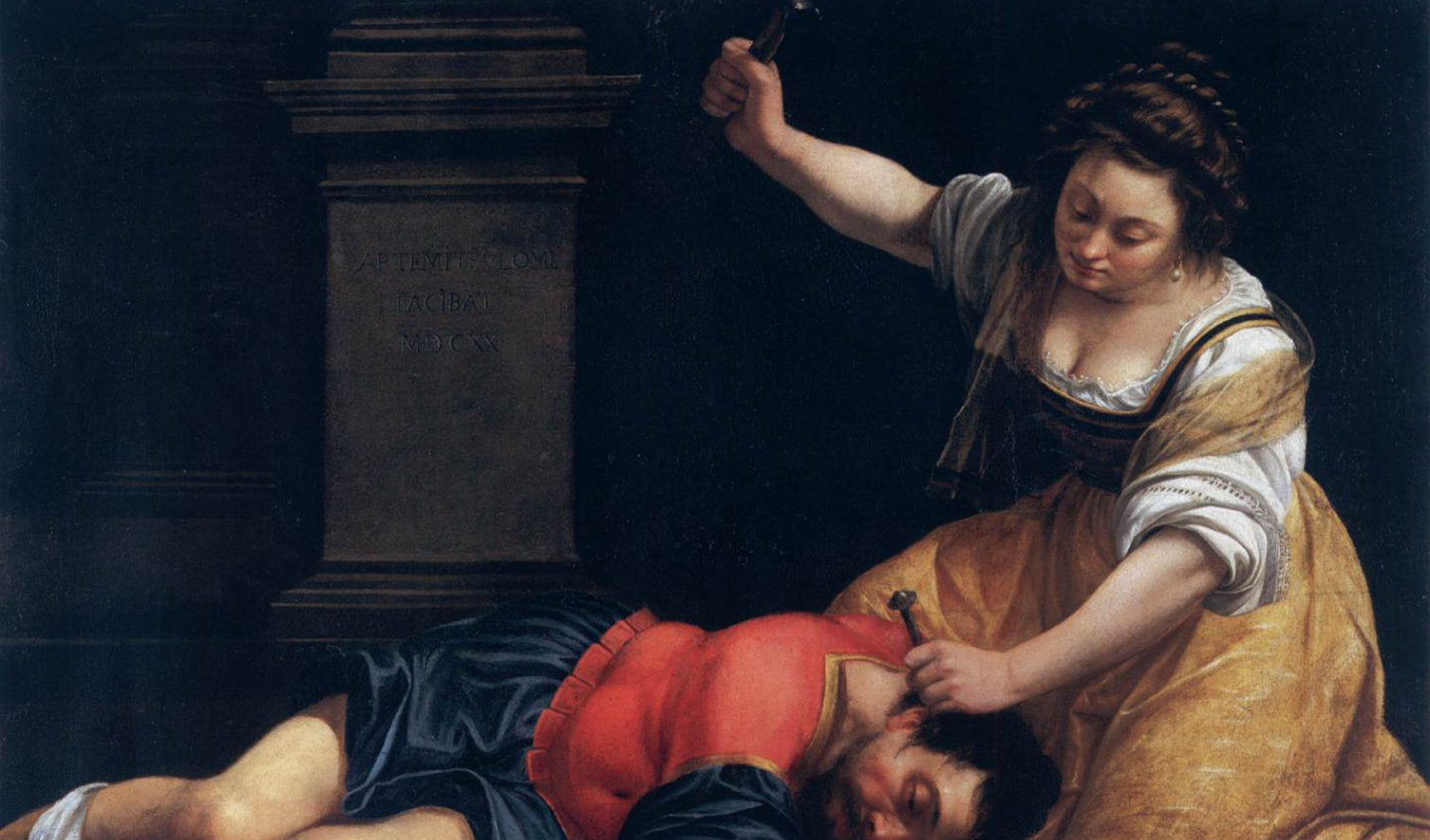

In 1611, Orazio was working with Agostino Tassi to decorate the vaults of Casino delle Muse inside the Palazzo Pallavicini-Rospigliosi in Rome. One day in May, Tassi visited the Gentileschi household and, when alone with Artemisia, raped her. Another man, Cosimo Quorli, was involved in the rape as well. With the expectation that they were going to be married in order to restore her dignity and secure her future, Artemisia started to have sexual relations with Tassi after the rape, but he reneged on his promise to marry Artemisia. Nine months after the rape, when he learnt that Artemisia and Tassi were not going to be married, her father Orazio pressed charges against Tassi.Orazio also accused Tassi of stealing a painting of Judith from the Gentileschi household. The major issue of the trial was the fact that Tassi had taken Artemisia's virginity. If Artemisia had not been a virgin before Tassi raped her, by the existing laws the Gentileschis would not have been able to press charges. During the ensuing seven-month trial, it was discovered that Tassi had planned to murder his wife, had engaged in adultery with his sister-in-law, and planned to steal some of Orazio's paintings. At the end of the trial Tassi was exiled from Rome, although the sentence was never carried out. At the trial, Artemisia was tortured with thumbscrews with the intention of verifying her testimony. After she lost her mother at age 12, Artemisia had been surrounded mainly by males. When she was 17, Orazio rented the upstairs apartment of their home to a female tenant, Tuzia. Artemisia befriended Tuzia; however, Tuzia allowed Agostino Tassi and Cosimo Quorli to visit Artemisia in Artemisia's home on multiple occasions. The day the rape occurred, Artemisia cried out to Tuzia for help, but Tuzia simply ignored Artemisia and pretended she knew nothing of what happened. Tuzia's betrayal and role in facilitating the rape has been compared to the role of a procuress who is complicit in the sexual exploitation of a prostitute. A painting entitled Mother and Child that was discovered in Crow's Nest, Australia, in 1976, may or may not have been painted by Gentileschi. Presuming that it is her work, the baby has been interpreted as an indirect reference to Agostino Tassi, her rapist, as it dates to 1614, just two years after the rape. It depicts a strong and suffering woman and casts light on her anguish and expressive artistic capability.

Florentine period (1612–1620)

A month after the trial, Orazio arranged for his daughter to marry Pierantonio Stiattesi, a modest artist from Florence. Shortly afterward the couple moved to Florence. The six years she spent in Florence would be decisive for both for Artemisia's family life and professional career. Artemisia became a successful court painter, enjoying the patronage of the House of Medici, and playing a significant role in courtly culture of the city. She gave birth to five children, although by the time she left Florence in 1620, only two were still alive. She also embarked on a passionate relationship with the Florentine nobleman Francesco Maria Maringhi.

As an artist, Artemisia enjoyed significant success in Florence. She was the first woman accepted into the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (Academy of the Arts of Drawing). She maintained good relations with the most respected artists of her time, such as Cristofano Allori, and was able to garner the favour and the protection of influential people, beginning with Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany and especially, of the Grand Duchess, Christina of Lorraine. Her acquaintance with Galileo Galilei, evident from a letter she wrote to the scientist in 1635, appears to stem from her Florentine years; indeed it may have stimulated her depiction of the compass in the Allegory of Inclination.

Her involvement in the courtly culture in Florence not only provided access to patrons, but it widened her education and exposure to the arts. She learned to read and write and became familiar with musical and theatrical performances. Such artistic spectacles helped Artemisia's approach to depicting lavish clothing in her paintings: "Artemisia understood that the representation of biblical or mythological figures in contemporary dress... was an essential feature of the spectacle of courtly life."

In 1615, she received the attention of Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger (a younger relative of Michelangelo). Busy with the construction of the Casa Buonarroti to celebrate his noted great uncle, he asked Artemisia—along with other Florentine artists, including Agostino Ciampelli, Sigismondo Coccapani, Giovan Battista Guidoni, and Zanobi Rosi—to contribute a painting for the ceiling. Artemisia was then in an advanced state of pregnancy. Each artist was commissioned to present an allegory of a virtue associated with Michelangelo, and Artemisia was assigned the Allegory of Inclination.

In this instance, Artemisia was paid three times more than any other artist participating in the series. Artemisia painted this in the form of a nude young woman holding a compass. Her painting is located on the Galleria ceiling on the second floor. It is believed that the subject bears a resemblance to Artemisia.[27] Indeed, in several of her paintings, Artemisia's energetic heroines appear to be self-portraits.

Other significant works from this period include La Conversione della Maddalena (The Conversion of the Magdalene), Self-Portrait as a Lute Player (in the collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art), and Giuditta con la sua ancella (Judith and her Maidservant), now in the Palazzo Pitti. Artemisia painted a second version of Judith beheading Holofernes, which now is housed in the Uffizi Gallery of Florence. The first, smaller Judith Beheading Holofernes (1612–13) is displayed in the Museo di Capodimonte, Naples. Six variations by Artemisia on the subject of Judith Beheading Holofernes are known to exist.

While in Florence, Artemisia and Pierantonio had five children. Giovanni Battista, Agnola, and Lisabella did not survive for more than a year. Their second son, Cristofano, died at the age of five after Artemisia had returned to Rome. Only Prudentia survived into adulthood. Prudentia was also known as Palmira, which has led some scholars to conclude erroneously that Artemisia had a sixth child. Prudentia was named after Artemisia's mother, who had died when Artemisia was 12. It is known that Artemisia's daughter was a painter and was trained by her mother, although nothing is known of her work.

In 2011, Francesco Solinas discovered a collection of thirty-six letters, dating from about 1616 to 1620, that add startling context to the personal and financial life of the Gentileschi family in Florence. They show that Artemisia had a passionate love affair with a wealthy Florentine nobleman, named Francesco Maria Maringhi. Her husband, Pierantonio Stiattesi, was well aware of their relationship and he maintained a correspondence with Maringhi on the back of Artemisia's love letters. He tolerated it, presumably because Maringhi was a powerful ally who provided the couple financial support. However, by 1620, rumours of the affair had begun to spread in the Florentine court and this, combined with ongoing legal and financial problems, led the couple to relocate to Rome.

Return to Rome (1620–1626/7)

Just as with the preceding decade, the early 1620s saw ongoing upheaval in Artemisia Gentileschi's life. Her son Cristofano died. Just as she arrived in Rome, her father Orazio departed for Genoa. Immediate contact with her lover Maringhi appeared to have lessened. By 1623, any mention of her husband disappears from any surviving documentation.

Her arrival in Rome offered the opportunity to cooperate with other painters and to seek patronage from the wide network of art collectors in the city, opportunities that Gentileschi fully grasped. One art historian noted of the period, "Artemisia's Roman career quickly took off, the money problems eased".

Large-scale papal commissions were largely off-limits, however. The long papacy of Urban VIII showed a preference for large-scale decorative works and altarpieces, typified by the baroque style of Pietro da Cortona. Gentileschi's training in easel paintings, and perhaps the suspicion that women painters did not have the energy to carry out large-scale painting cycles, meant that the ambitious patrons within Urban's circle commissioned other artists.

But Rome hosted a wide range of patrons. Spanish resident, Fernando Afan de Ribera, the 3rd Duke of Alcala, added her painting of the Magdalen and David, Christ Blessing the Children to his collection. During the same period she became associated with Cassiano dal Pozzo, a humanist and a collector and lover of arts. Dal Pozzo helped to forge relationships with other artists and patrons. Her reputation grew. The visiting French artist Pierre Dumonstier II produced a black and red chalk drawing of her right hand in 1625.

The variety of patrons in Rome also meant a variety of styles. Caravaggio's style remained highly influential and converted many painters to following his style (the so-called Caravaggisti), such as Carlo Saraceni (who returned to Venice in 1620), Bartolomeo Manfredi, and Simon Vouet.

Gentileschi and Vouet would go on to have a professional relationship and would influence each other's styles. Vouet would go on to complete a portrait of Artemisia. Gentileschi also interacted with the Bentveughels group of Flemish and Dutch painters living in Rome. The Bolognese school (particularly during the 1621 to 1623 period of Gregory XV) also began to grow in popularity, and her Susanna and the Elders (1622) often is associated with the style introduced by Guercino.

Although it is sometimes difficult to date her paintings, it is possible to assign certain works by Gentileschi to these years, such as the Portrait of a Gonfaloniere, today in Bologna (a rare example of her capacity as portrait painter) and the Judith and her Maidservant today in the Detroit Institute of Arts.

The Detroit painting is notable for her mastery of chiaroscuro and tenebrism (the effects of extreme lights and darks), techniques for which Gerrit van Honthorst and many others in Rome were famous.

Naples and the English period (1630–1656)

In 1630, Artemisia moved to Naples, a city rich with workshops and art lovers, in search of new and more lucrative job opportunities. The eighteenth-century biographer Bernardo de' Dominici speculated that Artemisia was already known in Naples before her arrival. She may have been invited to Naples by the Duke of Alcalá, Fernando Enriquez Afan de Ribera, who had three of her paintings: a Penitent Magdalene, Christ Blessing the Children, and David with a Harp.[36] Many other artists, including Caravaggio, Annibale Carracci, and Simon Vouet, had stayed in Naples for some time in their lives.

At that time, Jusepe de Ribera, Massimo Stanzione, and Domenichino were working there, and later, Giovanni Lanfranco and many others would flock to the city. The Neapolitan debut of Artemisia is represented by the Annunciation in the Capodimonte Museum. With the exceptions of a brief trip to London and some other journeys, Artemisia resided in Naples for the remainder of her career.

On Saturday, March 18, 1634, the traveller Bullen Reymes recorded in his diary visiting Artemisia and her daughter, Palmira ('who also paints'), with a group of fellow-Englishmen. She had relations with many renowned artists, among them Massimo Stanzione, with whom, Bernardo de' Dominici reports, she started an artistic collaboration based on a real friendship and artistic similarities. Artemisia's work influenced Stanzione's use of colors, as seen in his Assumption of the Virgin, c. 1630. De' Dominici states that "Stanzione learned how to compose an istoria from Domenichino, but learned his coloring from Artemisia".

In Naples Artemisia started working on paintings in a cathedral for the first time. They are dedicated to San Gennaro nell'anfiteatro di Pozzuoli (Saint Januarius in the amphitheater of Pozzuoli) in Pozzuoli. During her first Neapolitan period she painted the Birth of Saint John the Baptist now in the Prado in Madrid, and Corisca e il satiro (Corisca and the Satyr), today in a private collection. In these paintings Artemisia again demonstrates her ability to adapt to the novelties of the period and to handle different subjects, instead of the usual Judith, Susanna, Bathsheba, and Penitent Magdalenes, for which she already was known. Many of these paintings were collaborations; Bathsheba, for instance, was attributed to Artemisia, Codazzi, and Gargiulo.

In 1638, Artemisia joined her father in London at the court of Charles I of England, where Orazio had become court painter and received the important job of decorating a ceiling allegory of Triumph of Peace and the Arts in the Queen's House, Greenwich built for Queen Henrietta Maria. Father and daughter were working together once again, although helping her father probably was not her only reason for travelling to London: Charles I had invited her to his court, and it was not possible to refuse. Charles I was an enthusiastic collector, willing to incur criticism for his spending on art. The fame of Artemisia probably intrigued him, and it is not a coincidence that his collection included a painting of great suggestion, the Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (which is the lead image of this article).

Orazio died suddenly in 1639. Artemisia had her own commissions to fulfill after her father's death, although there are no known works assignable with certainty to this period. It is known that Artemisia had left England by 1642, when the English Civil War was just starting. Nothing much is known about her subsequent movements. Historians know that in 1649 she was in Naples again, corresponding with Don Antonio Ruffo of Sicily, who became her mentor during this second Neapolitan period.

The last known letter to her mentor is dated 1650 and makes clear that she still was fully active. In her last known years of activity she is attributed with works that are likely commissions and follow a traditional representation of the feminine in her works.

It was once believed that Artemisia died in 1652 or 1653; however, modern evidence has shown that she was still accepting commissions in 1654, although she was increasingly dependent upon her assistant, Onofrio Palumbo. Some have speculated that she died in the devastating plague that swept Naples in 1656 and virtually wiped out an entire generation of Neapolitan artists.

Some works in this period are the Susanna and the Elders (1622) today in Brno, the Virgin and Child with a Rosary today in El Escorial, the David and Bathsheba today in Columbus, Ohio, and the Bathsheba today in Leipzig. Her David with the Head of Goliath, rediscovered in London in 2020, has been attributed by art historian Gianni Papi to Artemisia's London period, in an article published in The Burlington Magazine.